What’s happening to men and women—and how to test before it’s too late

When Daniel, a 34-year-old lawyer, came in for his first consult, he looked exhausted. “I’m working out five days a week,” he said, “but I can’t put on muscle. My energy crashes by 3 p.m. And my wife jokes that I’ve lost my edge.” His bloodwork confirmed what I suspected: testosterone levels that would have been considered low for a man in his 50s just one generation ago.

On the other side, Clara, a 29-year-old teacher, had a different story: irregular cycles, weight gain around the middle, and anxiety that seemed to spike every month. Her gynecologist had recommended birth control to “regulate” things, but deeper testing revealed disrupted estrogen–progesterone balance and early signs of thyroid stress.

Daniel and Clara aren’t isolated cases. They represent what large-scale studies now show: men and women are hormonally imbalanced in ways our parents and grandparents weren’t.

Hormones under siege

The science backs this up. The Massachusetts Male Aging Study documented a steady decline in testosterone between the 1980s and early 2000s, not explained by age or body weight. A global meta-analysis found sperm counts have dropped by about 50% since the 1970s, with the decline now accelerating. For women, puberty is arriving earlier—roughly three months earlier per decade since the late 1970s—shaping hormone exposure over a lifetime in ways that raise risks of cycle disorders and metabolic disease.

What’s driving this shift? Researchers point to multiple layers:

Endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs): Phthalates, bisphenols (like BPA), and pesticides are now so widespread that the Endocrine Society has labeled them a major health threat.

Metabolic stress: Obesity and insulin resistance alter hormone-binding proteins, shifting estrogen–testosterone balance in both sexes.

Lifestyle disruption: Stress, blue light, and sleep loss spike cortisol and blunt anabolic hormones.

Developmental timing effects: Earlier puberty in girls and lower baseline testosterone in boys create long-term ripple effects for fertility, mood, and vitality.

The result? A hormonal landscape that’s profoundly different from a few decades ago.

The hidden cost of hormone imbalance

Why does this matter for you? Because hormonal health isn’t just about reproduction—it’s about quality of life. Low testosterone leaves men fatigued, unfocused, and at higher risk for cardiovascular disease. Estrogen and progesterone imbalance drives PMS, PCOS, thyroid issues, and mood instability in women. Left unchecked, these imbalances ripple outward: strained marriages, diminished work performance, even generational effects as parents pass along vulnerabilities to their children.

Daniel’s fatigue wasn’t just about the gym—it was about how he showed up at work and at home. Clara’s irregular cycles weren’t just an inconvenience—they were early warning signs her body was out of sync with its environment.

The DUTCH Test reveals what routine labs miss

Here’s the sobering truth: hormonal imbalance isn’t a fringe issue anymore. It’s the new normal. But normal doesn’t mean healthy.

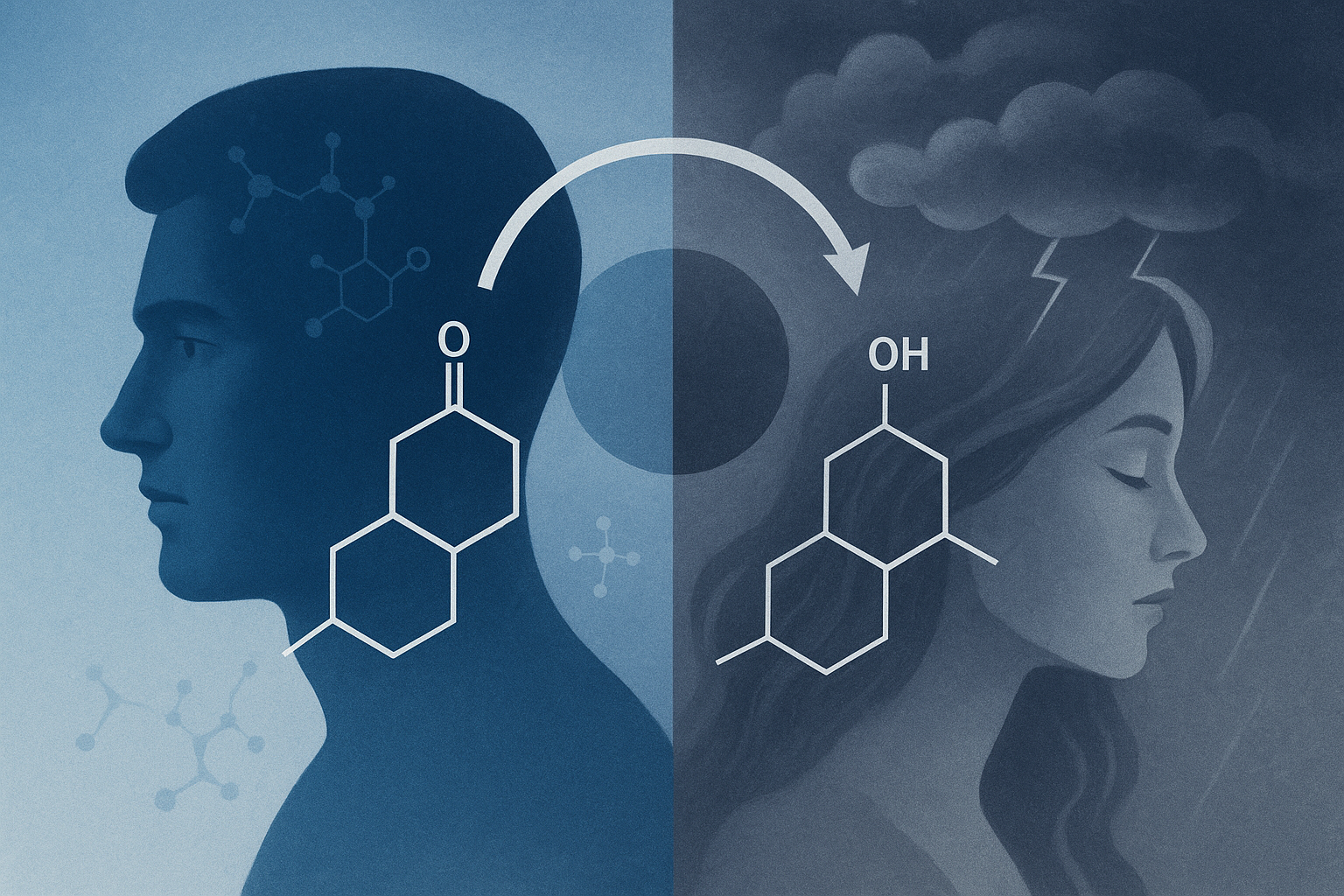

The smartest first step isn’t guessing—it’s testing. This is where the DUTCH Test (Dried Urine Test for Comprehensive Hormones) comes in. Unlike a standard blood draw, DUTCH captures not only your hormone levels but also their metabolites—showing how your body is actually using and clearing hormones. It measures sex hormones, adrenal stress hormones like cortisol, and even organic acids tied to metabolism.

That means a man like Daniel can see if his testosterone is being shunted down the wrong metabolic pathway, while a woman like Clara can uncover whether her estrogen dominance is paired with sluggish detoxification. Armed with this map, a practitioner can build a customized program—whether that’s nutrition, supplements, lifestyle changes, or targeted biohacking tools—to bring hormones back into balance instead of just masking symptoms.

So if you’ve been feeling “off,” stop guessing. The DUTCH Test is available for both men and women and offers a clear window into what’s really happening behind the scenes of your biology. Because the real question isn’t whether your hormones are under pressure—they are. The question is: will you take the step to measure them, so you can finally rebalance them?

Stay vital,

Richard Labaki

Holistic Therapist / Longevity Architect